In many parts of the world, men hold the power when it comes to choices about having and bringing up children. Gender inequality means adolescent girls and women often have little or no say in whether and when they have children, can access health services and get crucial support and care from their husband or male partner.

Born on Time is trying to shift those gender inequalities by empowering adolescent girls and women, changing community attitudes and engaging men as active partners of change. This can help to ensure power imbalances and harmful traditional practices end and the risk of preterm birth is reduced.

The What We Heard blog series gives a glimpse into the lives of women and adolescent girls in communities where Born on Time works in Bangladesh, Ethiopia and Mali, targeting preterm birth risk factors such as unhealthy lifestyles, maternal infections, inadequate nutrition and lack of access to contraception.

In the third and final blog of the series, we look at the role of male partners before, during and after pregnancy. Using focus group discussions in Bangladesh, Ethiopia and Mali, we asked adolescent girls and women who were pregnant or had a child in the previous two years to tell us about the engagement of their partner and how this impacted their health, reproductive outcomes and overall wellbeing.

Many girls and women in all three countries said they received help, care and understanding from their husbands and male partners. But too many others reported a different reality. Here are some of the things they told us.

Accessing health services, such as antenatal/postnatal care visits, nutrition and contraception advice, is crucial for mother and child before, during and after pregnancy. But some men in our program areas insisted on controlling this access or refuse to take part in the process.

Women in Bangladesh said their husbands don’t go with them to health centres because they “don’t have time” or “consider these as women’s jobs”. One said decisions about her health were made by her husband, father-in-law and brother-in-law. Another said “all decisions” in her community were made by males.

In Mali, adolescent girls said they could not visit a health centre without their husbands’ permission. One said that if the man cannot pay for health services, “then you stay at home”.

An adolescent mother said, “It is the husband who must give you permission and who must take you to the hospital.”

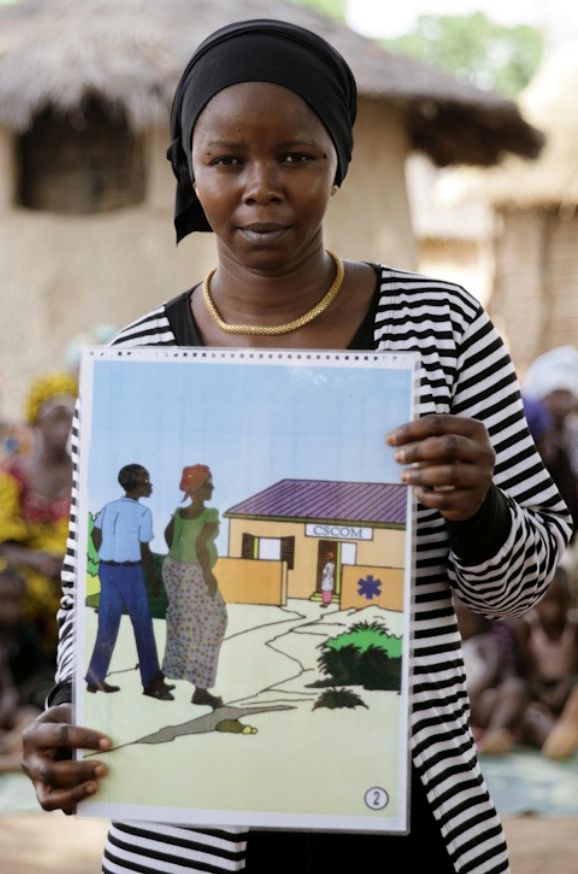

In Mali, a community leader explains what medical help is at hand locally, through imagery.

That view was shared by some Ethiopian women. One said her husband had to give permission but if he did not have the means to pay for health services then “the wife can go by herself”.

Born on Time has been working with adolescent girls and women to increase their access to sexual and reproductive health services. We do this through supporting the empowerment of women and adolescent girls, training birth attendants and health service staff on gender equality, and establishing women’s discussion groups. Born on Time staff also encourage men to accompany their female partners to health facilities to provide support.

It is vital that women and adolescent girls get the necessary rest during pregnancy and don’t carry heavy workloads, particularly in the last three months. But too many men don’t agree.

“Normally men have to help women but in our country it does not exist,” said a girl from Mali. Another added, “They say they have enough work to do.”

Lots of women in Ethiopia painted a similar picture. One said their own mothers were “the main supporters during pregnancy and delivery”. Another said, “Husbands do not care about their pregnant wife”. One Ethiopian woman revealed she got so little help that she gave birth “after spending the day weeding”.

In Mali, women reported doing heavy tasks while into late pregnancy. This included fetching water and wood, cooking and farm work. One said women want their partners to help “but unfortunately they do not and we cannot force them”. Pregnant women said they carried heavy loads up to 15km or walked long distances for water.

Most Bangladeshi women said husbands could do more to prevent pregnant wives from doing heavy physical work, such as carrying rice from fields.

At the same time, men who help their wives are often ridiculed. An Ethiopian mother said, “When people see my husband clean the floor, fetch water and cook, they laugh in contempt.”

Gashaw, 31, makes coffee for his wife, who is recovering from a miscarriage.

To combat these negative stereotypes, Born on Time has been engaging boys and men to be proactive partners of change. This includes training on gender equality, peer-to-peer training in schools and youth groups, and male discussion groups. In these groups, where the need for men to play greater roles in helping with household chores including childcare and giving opportunities for the pregnant woman to rest is stressed.

Many women—particularly in Bangladesh—reported being well looked after and supported in the days and weeks following delivery of their baby. But too many said they were expected to go back to work very quickly.

“After childbirth, as long as we are not dead, they don’t care,” said a woman from Mali. Another said that “apart from making us pregnant, men don’t do anything for women.”

In Ethiopia, women said they are required to work “as soon as we spend the three or four days of rest”.

Male attitudes like those outlined above still persist in many parts of the world. Born on Time aims to change those beliefs by engaging men as active partners of change who support their wives in equal relationships. The outcome would be gender-equitable partnerships where both partners make joint decisions about sexual and reproductive health issues, where household duties are shared and where equal power dynamics prevail.

Mostakim, age 32, helps his wife, Marufa, age 25, cook nutritious food while she breastfeeds their three mont-old baby.

This means encouraging and educating men to take a full and active involvement in roles that are often not traditionally considered to be in the male domain—from family planning and pregnancy to childbirth and raising and caring for the child.

Having children too young and too soon after previous births, or combining pregnancy with heavy workloads can have serious health consequences for both mother and child. But many women have little or no say in when they have children.

“I was forced to deliver by my family and his family without my willingness,” said an adolescent girl in Ethiopia. An older woman in the same country echoed that, saying, “I was not interested in giving birth. I was pressured by both families.” Fear of divorce or being kicked out of the home were given as reasons for having children.

In Mali, many women said their husbands decided when to have children. One teenager said men “do not accept” birth control and added, “That is why there are women who have many children”. Another said she would be divorced if she was “unable to give birth at the expected time”.

Most Bangladeshi girls and women interviewed said it was a joint decision. But not all—one shared that, “I don’t have any decision – it all belongs to my husband.”

Born on Time works in these communities to change the mindsets of men—who in most cases are the decision-makers in the families—to empower girls and women, and to encourage equitable decision-making and more equal power dynamics within the household.

Publié:

mai 29, 2019

Auteur:

Jessica Bryant, Head of Communications, Media and PR, Save the Children Canada

Catégories:

Partager cette publication: